The Los Angeles River

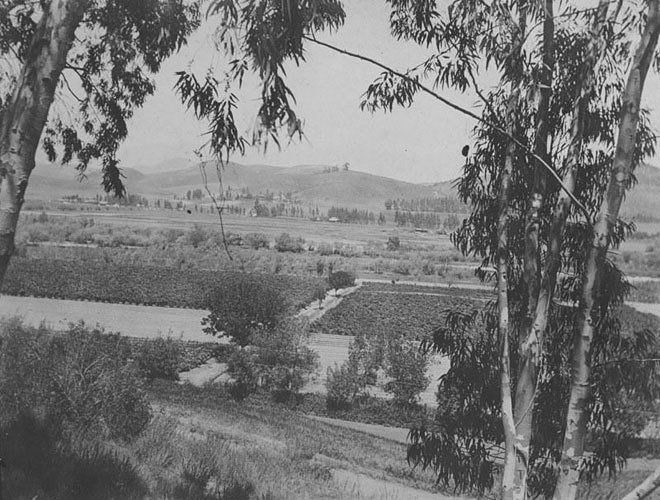

The Los Angeles River was once the centerpiece of a flourishing Los Angeles region.

“A very lush and pleasing spot, in every respect [...] southward there is a great extent of soil, all very green, so that really it can be said to be a most beautiful garden.”

When Spanish colonizers initially encountered the landscape, they described it as a riot of wildflowers, wild grapes, sage, rose bushes, and sycamore trees. In 1781, the great beauty and bounty of the Los Angeles River inspired the city’s founding on its banks.

Wetlands including river systems clean and infiltrate more water, cleanse more air, sequester more greenhouse gasses, and support more species than any other land type in the Los Angeles Region. However, today less than 5% of these resources remain.

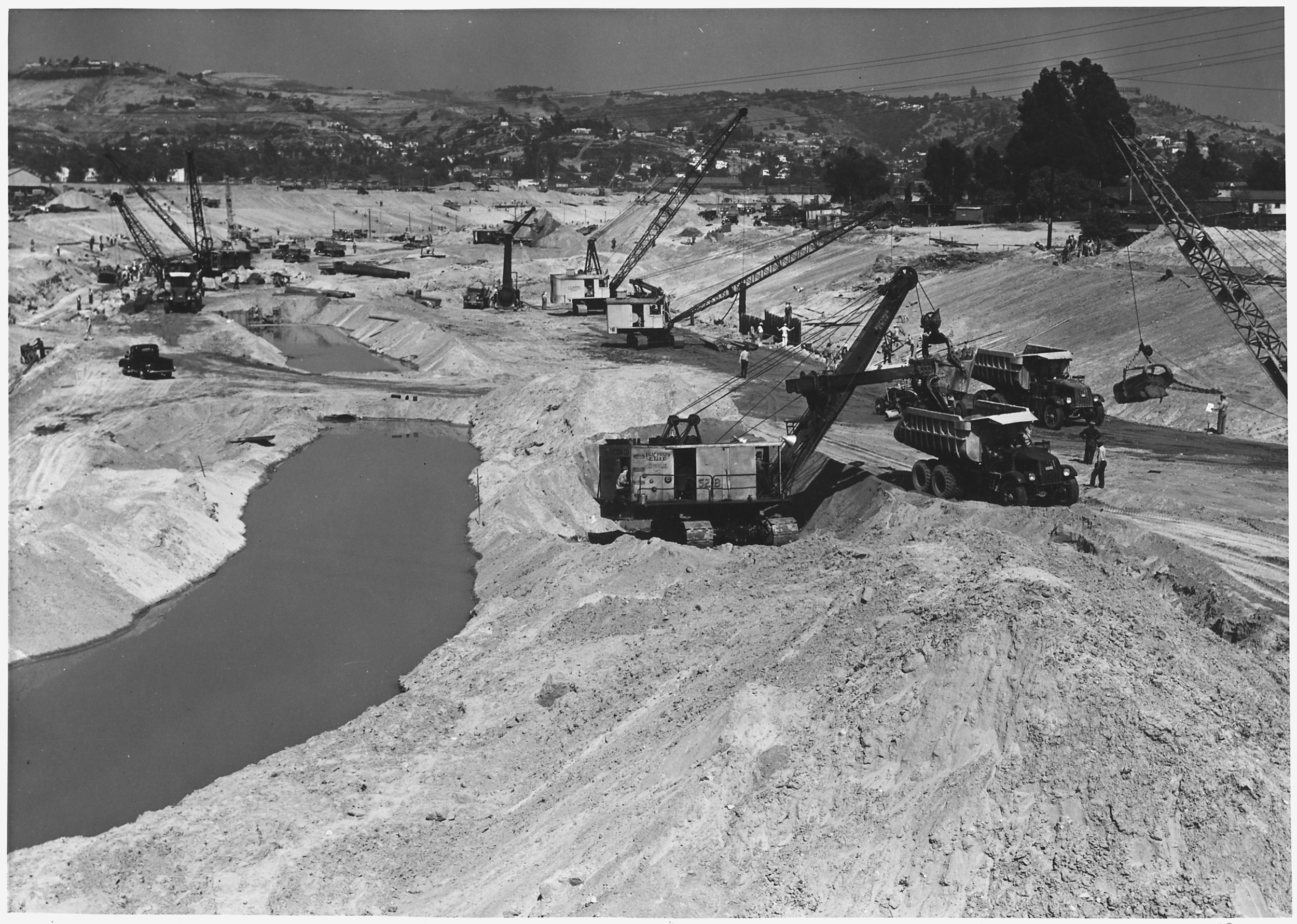

In the 1930’s, the city of Los Angeles had rapidly expanded into the areas of the river which were known to be prone to flooding. The conflict between the city’s heedless development and the river’s unpredictable nature, led the region’s leaders to partner with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to confine all the river’s waterways with cement encasing, fixing its course within a concrete straitjacket and defining a new standard for water management in the region for generations to come.

“I lived my Tom Sawyer youth on the Los Angeles River [...] before the ‘big paving extravaganza.’ [...] We slept overnight in the river bed most of the summers [in the] dry, clean white sand. ”

Contrary to popular belief, Los Angeles is not a desert. Angelenos live in a mediterranean climate with seasonal rainfalls concentrated between October and March. The region’s average annual rainfall amounts to approximately 12” a year near the coast and 15” around downtown Los Angeles. In the mountains of the region, rainfall ranges from 35” to 52” each year. Historically, more than 80% of the region’s rainfall was infiltrated to local groundwater basins.

In an average year, now approximately 600,000 acre-feet (196 billion gallons) of precious rainwater is channeled to the ocean. This is comparable to the amount the Los Angeles Basin imports from Northern California and the Sierras—approximately 750,000 acre-feet (244 billion gallons). Los Angeles may have enough water with better land management and conservation, but not enough to waste.

In 2012 to 2017, we saw the effects of the last century’s water management practices come to a head as California and the Los Angeles region suffered from the largest drought in recorded history. This and other factors forced the region to reconsider its stance on water management. The region is moving toward comprehensive watershed management practices, where the entire watershed, not just the river, is taken into consideration to evaluate and develop not only wholistic water management practices but also climate resilient communities.

The choices we make about the Los Angeles River determine the city’s economic viability and social health. The benefit of a concrete river is singular—it swiftly transports rainwater out of the city and into the ocean—yet deprives the city of all other essential ecosystem services. We now understand, from examples across the world, the critical need for protecting floodplains as part of reliable, regenerative flood management strategy.

The USGS projects that a large flood event like the storms of 1861-1862 are as likely to occur as the biggest possible earthquake, and would result in three times the damage. Hundreds of thousands of parcels of land are already threatened across the region. Proactive management is key. The National Institute of Building Sciences 2017 study evaluated 23 years of federally funded mitigation grants and found that the nation can save $6 in future disaster costs for every $1 spent on hazard mitigation. Proactive action saves lives, and also saves several times the funding and resources otherwise necessary to react to disaster.

Soil and plants of riparian systems are the most suitable and most effective use of the land, and development in these places is most unsuitable. In a region facing our rising challenges this understanding must drive policy, planning, and development.

Living rivers and healthy watersheds provide profound benefits to the cities they nurture. They provide water supplies, filter out water and air pollutants, move sand to ocean beaches building coastlines, provide critical habitat, sequester carbon and other greenhouse gasses, regulate floodwaters, and create cooling oases for relaxation and recreation. We have an imperative to prioritize the health of the river and its contributing watershed over business as usual, and to make the complex decisions necessary to take regenerative actions that will provide for generations to come.

With vision and long-term perspective, we can start to take action now so that communities are not more adversely effected. Comprehensive engagement, conversations, plans, and programs can step by step reach an equitable future, and a regenerative Los Angeles. We can provide support for communities to shift organically over generations instead of as mandates following terrible disaster. If we develop and retrofit land to capture water we can reduce the intensity of flood waters, and peel back concrete to enable all of the essential functions rivers and soil can provide.

Banner image by Smjafry (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons